Galvanic Corrosion

Three ways to prevent it

A frequently asked question in the context of metal connections is how dissimilar metals behave and whether galvanic corrosion can take place, for example, between carbon steel and stainless steel, or aluminium and carbon steel. The short answer to this question is: usually, galvanic corrosion is not a problem.

The long answer is: for galvanic corrosion to take place, the following three conditions need to be met simultaneously:

different types of metals;

presence of an electrolyte (e.g. water);

electrical continuity between the two metals.

Types of metal

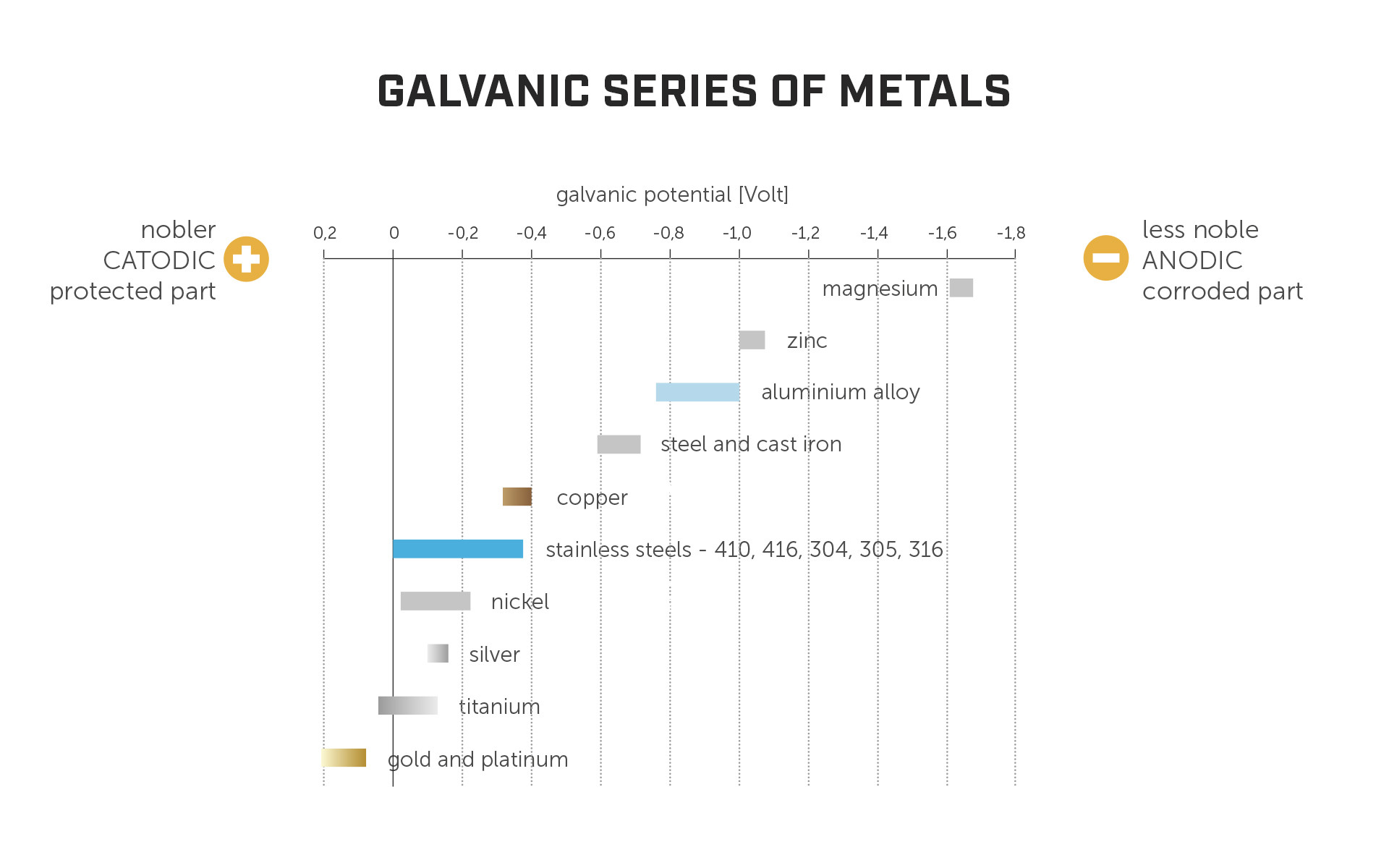

The potential for galvanic corrosion between metals is dictated by how far apart they are on the galvanic series of metals. The higher the potential difference, the higher the risk for corrosion to take place.

The most common structural materials in timber buildings are stainless steel, carbon steel, aluminium, and zinc (as a coating for carbon steel). The fact that zinc is commonly used in close contact with steel as a coating provides us with a couple of interesting insights:

in principle, combining dissimilar materials is not a problem. Zinc doesn't start to deteriorate automatically as soon as it comes into contact with steel;

zinc is less noble than steel (i.e., further to the left on the above chart) and therefore acts like a sacrificial layer to prevent steel corrosion, because noble materials “corrode” less noble materials.

The electrolyte

One of the three conditions for galvanic corrosion to take place is the presence of an electrolyte. The electrolyte allows the transfer of ions between metals, which facilitates the electrochemical reaction that leads to corrosion. Water is one of the most common electrolytes and if you keep water out of the connection, you prevent galvanic corrosion from taking place.

But, doesn't wood contain moisture that could potentially act as an electrolyte and trigger galvanic corrosion? Even after years in a closed environment, timber only reaches an equilibrium moisture content, but it will never reach 0% moisture content. At this point, it's important to distinguish between free water and bound water. Free water could potentially act as an electrolyte, but in this case, the risk associated with it would be extremely low, because the electrolyte needs to touch both dissimilar materials, and free water is not exactly pouring in streams out of the wood cells. Bound water in turn can't act as an electrolyte because it is bound within the cells of the timber. It's safe to say that there's no free water left in timber with a moisture content below 20% and given that the moisture equilibrium of timber is closer to 10%, the timber that surrounds the connection can actually protect the connection from galvanic corrosion by absorbing excess moisture and prevent a buildup of water.

Three prevention methods

Sometimes we cannot avoid using dissimilar metals. Or, by using a mix of different metals, we yield efficiencies for the project and we don't want to give up on those. And we don't need to give up on them if we adhere to a few principles:

KEEP THAT WATER OUT. No water, no electrolyte, so no galvanic corrosion. Water is not only a problem for galvanic corrosion, but also for conventional corrosion, swelling and deformation of the timber, rot, stains and fungi. Actually, with water in the structure, galvanic corrosion can be the least of your concerns.

Insulate dissimilar materials, i.e., break the electrical continuity between the materials. For example, LOCK EVO is made of extruded aluminium and is used with stainless steel screw fasteners. The aluminium plates are painted to avoid galvanic corrosion.

Make sure fasteners are the more noble material in the connection. For example, our concealed hangers plates in aluminium use carbon steel screws and dowels (where applicable). Carbon steel and aluminium don't have too high a potential difference on the galvanic series; corrosion is therefore unlikely and even if it takes place, it's very slow. Moreover, since carbon steel is the nobler material, it is not the aluminium connector that cuts through the small-diameter fasteners and immediately endangers the structural integrity of the connection. The small-diameter fasteners are the ones that corrode the less noble aluminium; thus, visibly displacing the connection before it reaches catastrophic failure.

In conclusion, the most commonly used materials in timber construction do not show a significant risk for galvanic corrosion if we follow the basic principles, the first being keeping water out of the structure. The theoretical considerations outlined in this article are backed up by Rothoblaas' thirty years of experience in testing and in producing structural solutions for timber construction.

All rights reserved

Technical Details

- Country:

- Any

- Products:

- LOCK T EVO ALUMIDI